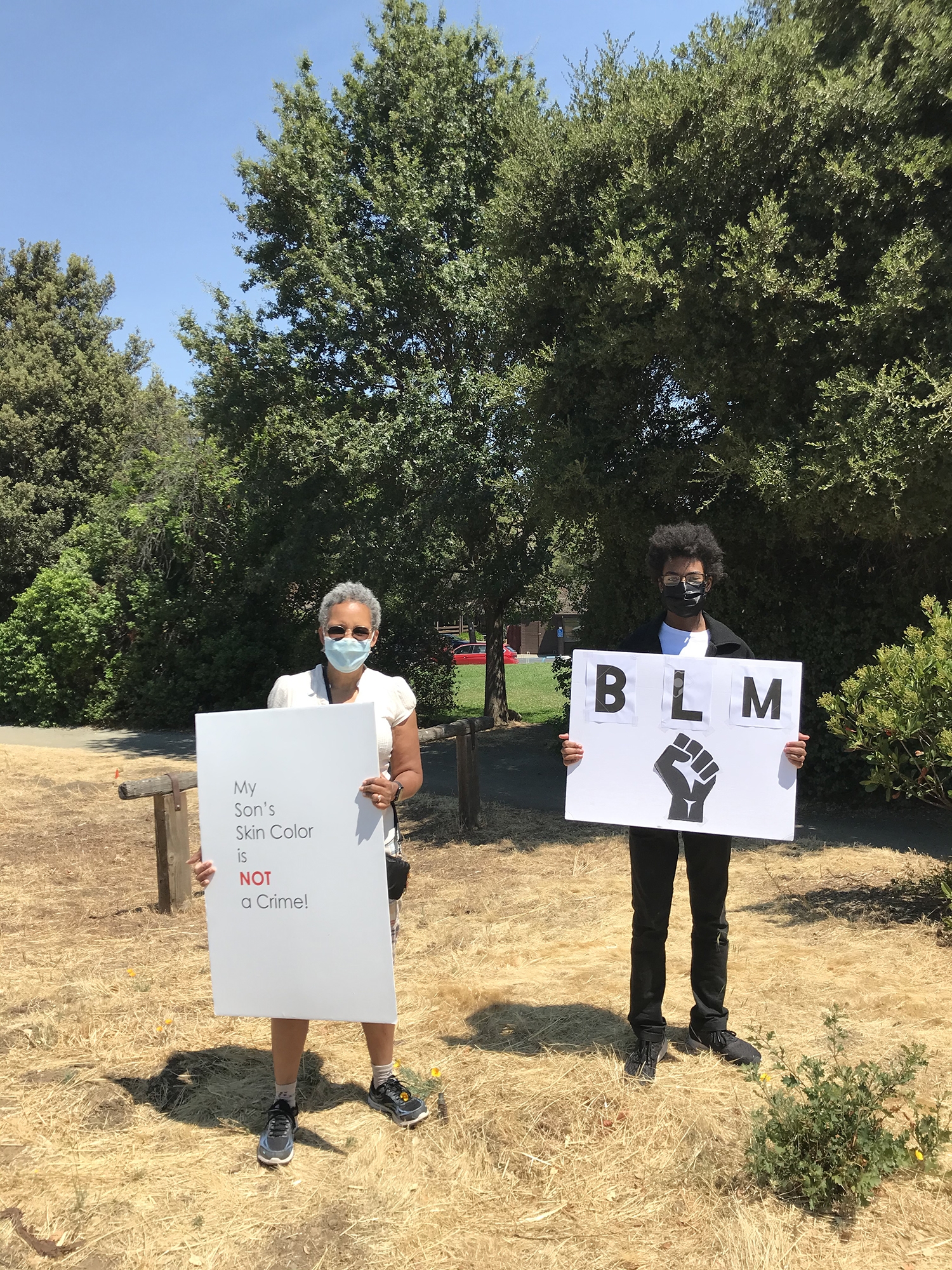

Every Sunday morning at the corner of Alpine and Portola roads in Portola Valley near Roberts Market, a handful of people meet to demonstrate support for the Black Lives Matter movement.

The group started meeting shortly after Minneapolis police killed George Floyd, an unarmed Black man, in late May. They formed in June after the eruption of "so much conversation and demonstration throughout the country," said Lucy Neely, Neely Wine's sales and marketing director and a Portola Valley resident. She and her wife felt bereft at the lack of any visible public discourse in town on racism, she said.

"One night my wife said 'we've got to do something,' so I just put a notice out on our community Listserv inviting people to gather in solidarity with BLM that Sunday," Neely said in an email.

Dr. Judith Murphy, a longtime Portola Valley resident, also suggested the idea on Portola Valley Forum, an email forum for residents and members of the Portola Valley community. The group has continued assembling every week for eight months.

"It feels important to me to continue to bear witness," she said. "Lots of people go by that corner. We get a lot of reactions: thumbs up and thumbs down, 'go home' and 'thanks for doing this.'"

Over the summer and fall, attendees also met for an hourlong socially distanced "Whiteness Discussion Group" after the 11 a.m. protests, though they discontinued the discussions in October when the weather got colder and attendance dwindled. The rallies maxed out in size with about 100 people and now draw about seven to eight core members every week, said resident Kim Marinucci Acker, who facilitated the discussion group.

"The focus was really on looking at ourselves and what is the culture of whiteness, and how do we act out these behaviors in our blindness because we never talk about whiteness?" Acker said.

Neely said uncovering racial biases, and talking about them, is delicate, important work.

Reactions from passersby

Dr. Gwen Stritter, a Portola Valley resident since 1981, joined the protests over the summer. Stritter, who is Black, said the predominately white community has been very welcoming to people of color over the years, in general. The latest census data from 2018 shows 81% of the town's residents at the time were white, 7.3% were Asian, about 6% were Hispanic, 4% were multiracial and just 14 people identified as Black.

Stritter said the group sometimes would get negative feedback. These passing bicyclists and drivers shook their fists, called the protesters "commies" and said things like "you'll believe anything you see on TV."

"I could tell you a couple times, standing on the corner holding up my sign demonstrating, you could see the other side of Portola Valley," she said. "I know not all people agree with Black Lives Matter, but some people got pretty aggressive."

She said in the past when she was part of discussions with white people about race, Black people were expected to lead them through meetings and set the tone.

"It's the first time I've been part of a group of white people who, on their own, decided to do this (talk about race)," she said, which impressed her. "What it was, was people decided to not stand by silently and unwittingly continue the social habits/behaviors that create racial discrimination in this country. These are people who are really determined to examine themselves for their unconscious biases; it blew me away."

It also stands out to Stritter that white people are starting to wrestle with how discrimination has played out in the Portola Valley community, not just in the rest of the country. For example, housing laws restricted where people of color were allowed to buy homes on the Midpeninsula in the past.

Why Portola Valley?

Acker said she thinks protests have been held in smaller towns as a result of the COVID-19 pandemic.

"I was too afraid to go to San Francisco or Palo Alto because of the virus," she said. "I knew I could go down there (to Alpine and Portola roads) and I could imagine being able to distance myself. A lot of people had that same kind of feeling. With the outrage and heartbreak, it became something else; many friendships forged over these months."

Portola Valley felt like a "silly" place to hold the protests at first, she said.

"Portola Valley? Seriously, come on," she said. "It's a predominantly white community, the fourth most affluent city in the U.S. How is this (racism) relevant here? It's everywhere there's no place that is exempt. It's in me. It's all around us. It's the water we swim in."

Acker said that about a half year before the protests began, she felt fear when a Black man pulled up next to her in the parking lot for a hike.

"Then I immediately felt ashamed," she said. "I didn't like it in myself. I got out of my car and started talking to the guy. But I overfocused on my shame. There I am making it all about me again" which gets in the way of working on dismantling white supremacy, she said.

"There are deep patterns that have been implanted in us (for) generations; they're passed down in subtle ways," Acker said.

She said she was recently driving down Alpine Road when she saw a Black man to her left riding his bicycle. She felt a neutral response. When she looked to her right she saw a white man jogging.

"I had a visceral response that (the white man) was the scary person," she said. "I thought, 'Wow, this is the first time I've had even just a taste of what it feels like to be Black in America.'"

She said this response to the white man may have been influenced by the storming of the Capitol in January by a group that included white supremacists.

"A lot of it has to do with our political climate," she said. "We're seeing white supremacy come out of the woodwork."

Portola Valley resident Johnny Clark, 14, a freshman at Eastside College Preparatory School in East Palo Alto, has been attending the rallies since September with his grandparents (who stay in the car because of COVID safety concerns).

Clark said he had a few uncomfortable racially charged experiences while attending middle school in Woodside. Even though he wasn't the only person of color in his classes, he would often be the only Black student. Some students freely used the N-word, including a girl who sometimes bragged that she was a person of color so she could say it and white students couldn't, he said.

"I felt uncomfortable with it; I don't even use it," he said.

Seeing Floyd's death on camera motivated Clark to get involved in BLM. He'd spoken up about racial injustice with other students who he said would say things like "All lives matter" and described Clark as "intense" about his conviction about BLM.

"That doesn't justify a Black man getting killed in the street for no reason," he said of his classmates' comments. Fellow students seem to finally be understanding, he said.

"Going (to the rallies) and seeing people who really want to make a change and really care about my culture and my color and my race, it's very heartwarming to see and that they aren't faking it," he said.

Group achievements

If nothing else, some Portola Valley youth have received the message that there are people in this community that care about racial justice, Neely said.

"This feels important to me, having grown up here," she said. "Also, some people were annoyed. We get snarky emails, public and private, and salty people flipping us off as they go through the intersection. I think it's fine or even important for people to feel uncomfortable in these ways. Our intention isn't for it to be a partisan issue, though. The intention is for our demonstrations to be giving energy to universal human values justice, dignity, peace, equity. So hopefully our efforts have moved the needle on those issues in some hearts, even a tiny bit."

Neely said it's going to take as much effort to dismantle white supremacy as it has taken to create it.

"If our efforts are just a flash in the pan when it's popular, then we're not going to get far," she said. "And what we've seen is that there is energy in this community to do this kind of work, and that more structure would help facilitate that. As a group we're currently listening to see where to put our energy and efforts in the future. Do we keep demonstrating on the street corner every Sunday? Do we advocate for the official creation of a justice committee in Portola Valley that will continue to focus on these topics?"

Acker said that going out every Sunday, they get a pulse on how people are feeling about this issue. She's seen "haters" respond to the protests in a way that she had only previously seen on TV.

Acker has been most moved by the responses of children to the protests. She recalls a little girl sitting in the backseat of her parents' car, making the shape of a heart with her hands as they drove by the demonstration.

"It gives me hope; seeing that kind of thing happening over and over," she said.

Did she expect to see the longevity of the Portola Valley protests?

"No way," she said.

Comments

Registered user

Portola Valley: other

on Feb 26, 2021 at 12:19 pm

Registered user

on Feb 26, 2021 at 12:19 pm

Angela, thank you so much for the opportunity to share my experiences. This was an excellent article (I'm probably just biased LOL).

I don't mean to advertise here, but everyone is welcome to the corner to protest with us every Sunday.

Thanks again.

Sincerely,

Johnny

Registered user

Portola Valley: Central Portola Valley

on Feb 28, 2021 at 9:48 am

Registered user

on Feb 28, 2021 at 9:48 am

The photos attributed to me were actually taken by Kim Marinucci Acker. She shared them with me and I shared them with MS Schwartz when she contacted me for the article. Thanks to the Almanac for recognizing our ongoing commitment to this important cause. Judith Murphy

Registered user

another community

on Mar 1, 2021 at 4:17 pm

Registered user

on Mar 1, 2021 at 4:17 pm

Thanks for the interview, Johnny! Judith, I've updated the photo credits.